RachelBostwick / Pixabay

A guest post by children’s book authors Sally Loughridge Ph.D. and Judith Wolf Mandell

A child’s age and mastery of developmental stages in the physical, cognitive, and emotional realms can affect the way he or she responds to serious physical challenges. In addition to treatment and support from sensitive professionals and caring family, children’s literature can provide a valuable resource for children in difficult health situations.

Let’s imagine . . .

- You are a small child who has just mastered walking. You toddle and fall, each time rising to explore further. But after a much harder fall, you break your leg and find yourself in a chest-to-ankle spica cast that sidelines you from your usual active life. You can’t understand your parents’ reassurance that the cast will come off in a month. The days drag by and you become sad, frustrated, and cross.

- You are a middle school child who is gaining success, attention, and confidence in sports. After becoming unusually fatigued, you are diagnosed with a life-threatening disease. The treatment leaves you feeling nauseous and even more exhausted. Unable to compete on the playing field, for now, you feel left out, angry, and incompetent.

- You are a young teenager anxious about acceptance among your peers. Even with ongoing treatment by a dermatologist, ugly acne erupts over much of your face. You try hair styles to hide your pimples. You shun contact with others to avoid being teased. Despite reassurance from your parents and doctor, you think you will be marred and rejected for the rest of your life.

Serious injury or illness and subsequent treatment often cause a child pain and deal at least a temporary blow to regularity and quality of life. Even an ailment that typically plagues a given age group may disrupt a child’s steadiness and happiness.

As a child grows, mastery of developmental steps in the physical, cognitive, and emotional realms has a significant influence on the ability to cope with a serious injury, illness or ailment. In a sibling of a hurting child, developmental maturity will also impact how he or she can take in and understand a brother’s or sister’s situation.

Disruption in development

Renowned Swiss psychologist Erik Erikson identified these key psychosocial tasks as a child grows.

- The infant: Developing a sense of basic trust

- The toddler: Developing independence and self-confidence

- The preschool child: Developing the ability to initiate tasks and learn greater self-control

- The elementary age child: Developing a sense of competence and adequacy

- The teenager: Developing a sense of self and identity

An injury or illness that disrupts an expected stage of development may aggravate a child’s response to the situation, prompt regression to less mature behavior, and even hinder recovery. Consider again our three imaginary situations.

- For children who have just learned to walk, a physical injury like a broken leg will curtail the way the way they can move and explore and may cause them to grow grumpy or glum. Unable to cognitively understand time yet, toddlers will not be able to foresee when pain, treatment, or restrictions will end.

- School-age children enjoying increasing physical prowess may respond to bodily trauma with a wavering sense of competence and feelings of inferiority.

- Adolescents disfigured by injury or slowed by illness may struggle with peer relationships and self-acceptance. When physical appearance is a major factor in self-esteem, even an adolescent ailment such as severe acne can undermine a teen’s sense of identity and confidence, and for some, trigger depression.

Just as the integrity of a house depends on a solid foundation, so too does a child’s healthy growth. The child who, by virtue of age, has not yet mastered the sequence of developmental stages will naturally have less ability to understand and cope with physical insults. In addition to developmental status, a child’s overall resilience—spirit and spunk—will affect his or her response to severe illness, ailment, or injury.

Literature as a resource

A strong and stable family life will bolster the child. Many other resources can help stricken children cope as well. Beyond excellent physical treatment, child life specialists, pediatric nurses, social workers, psychologists, and counselors can provide critical assistance. By taking into account developmental status and emerging personality as well as the type of illness or condition, these professionals can further tailor their interventions to an individual child.

Specialized children’s literature, from picture books to teen novels, provides a complementary resource to help children and families cope with a serious physical challenge and the treatment it may entail. Readily accessible, books are a familiar means of learning and enjoyment.

Check your public, school, or hospital library to find books that may help your child, or one you know, cope with the psychological impact of a serious illness, injury, or ailment. You can also find such books by asking the pediatric specialists or by searching the internet.

About the authors and their children’s books

Sally Loughridge is a professional artist living on the coast of Maine. She previously practiced clinical psychology for more than 25 years.

Judith Wolf Mandell is a writer who has had a varied career as a journalist and public relations professional. She, her husband, and their Cockapoo live in a hilltop home in the woods in Nashville, Tennessee.

Sally and Judith have each written a book designed to help support children dealing with a serious injury, illness, or ailment.

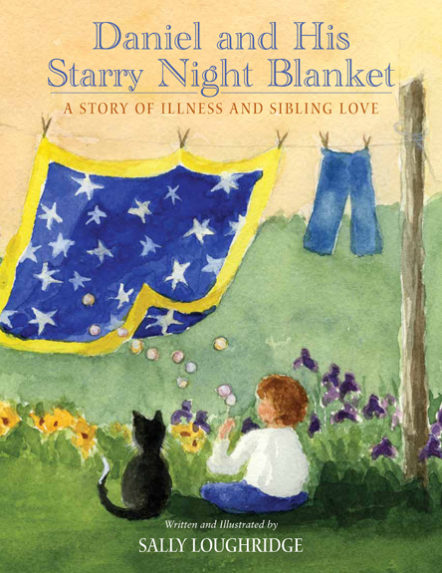

Sally wrote and illustrated Daniel and His Starry Night Blanket: A Story of Illness and Sibling Love. It tells the story of a preschool child whose older sister gets cancer and, from his perspective, far too much of their parents’ attention. The book has a loving, generous ending.

Sally wrote and illustrated Daniel and His Starry Night Blanket: A Story of Illness and Sibling Love. It tells the story of a preschool child whose older sister gets cancer and, from his perspective, far too much of their parents’ attention. The book has a loving, generous ending.

Sally, who is a cancer survivor, also wrote the book Rad Art: A Journey Through Radiation Treatment. It presents her visual and written diary kept over 33 consecutive days of radiotherapy.

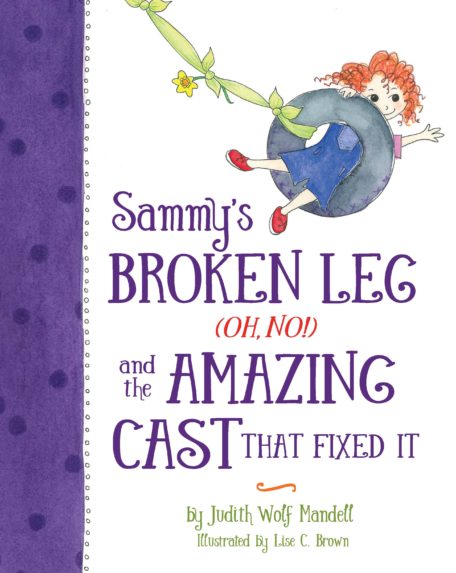

Judith’s book Sammy’s Broken Leg (Oh, No!) and the Amazing Cast That Fixed It was inspired by her preschool granddaughter’s fall that broke her femur, landing her in a spica cast for a mostly miserable month. Her first book is a whimsical cheer-up story for glum, grumpy kids in cumbersome casts.

Judith’s book Sammy’s Broken Leg (Oh, No!) and the Amazing Cast That Fixed It was inspired by her preschool granddaughter’s fall that broke her femur, landing her in a spica cast for a mostly miserable month. Her first book is a whimsical cheer-up story for glum, grumpy kids in cumbersome casts.

The authors also recommend the book Zitface by Emily Howse. The main character, Olivia, becomes depressed, withdrawn, and ashamed because of acne. With support from an empathic peer, she decides to stop letting it control her life. Emily is a licensed mental health professional, who struggled with acne after college. “. . . it would have been worse had it occurred when I was thirteen,” she said.